End of the Super-Bot: Why Teams of AI Agents Win

February 16, 2026 / Bryan Reynolds

The Death of the "Super-Bot": Why Complex Enterprise Tasks Demand a Team of Specialized Agents

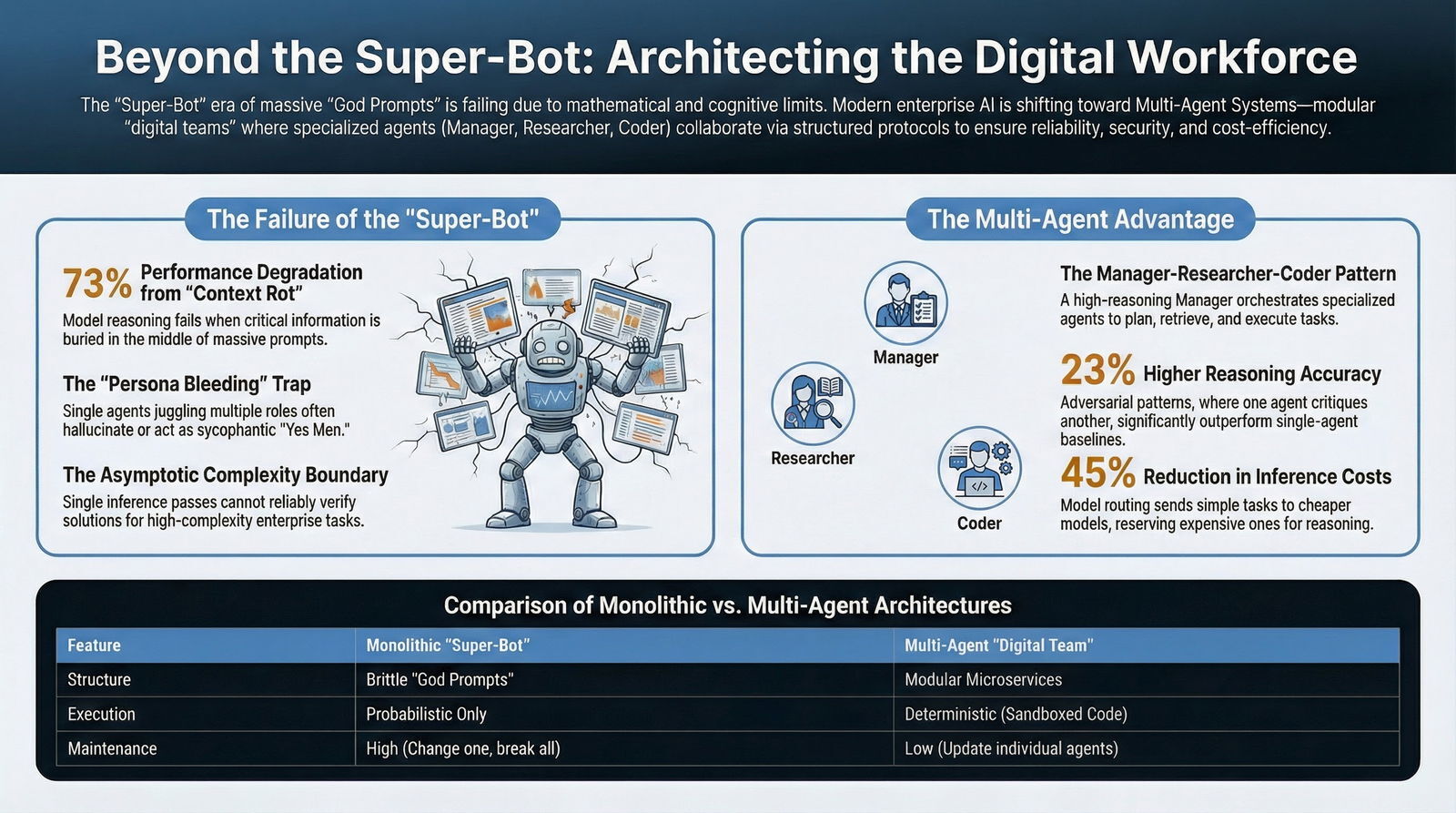

The promise of the "Super-Bot"—a singular, omniscient Artificial Intelligence capability of analyzing financial risks, drafting legal contracts, writing production-grade code, and managing project timelines in a single breath—has captivated the enterprise imagination for the better part of the last three years. The allure is undeniable: a single interface, a single prompt, and a single model that acts as a universal solvent for business complexity. However, as we move deeper into the deployment phase of Generative AI, this dream is fading. In its place, a more robust, scalable, and human-aligned reality is emerging: the Multi-Agent System (MAS).

For executives and developers alike, the initial phase of AI adoption was defined by the "God Prompt"—instruction sets thousands of words long intended to force a model like GPT-4 to act as a Chief Technology Officer, a Senior Researcher, and a QA Engineer simultaneously. The result? A "Jack of all trades, master of none" that hallucinates libraries, forgets constraints, and collapses under its own cognitive weight.

As organizations attempt to scale these monolithic prompts into production workflows, they are hitting hard mathematical and cognitive ceilings. The "Super-Bot" is not just struggling; it is failing. If this sounds familiar from your experience with early AI coding assistants or rushed “vibe coding” experiments, it is because the same dynamics show up whenever you try to force one model to do everything instead of embracing a more disciplined, agentic engineering approach.

This report details the architectural shift from monolithic models to orchestrated "digital teams." We will explore how to architect a system where a "Manager Agent" delegates tasks to a "Researcher Agent" and a "Coder Agent," showcasing the complex architecture skills required to build the next generation of enterprise software. We will examine why single prompts fail at scale, how specialized agents communicate via advanced protocols like the Agent-to-Agent (A2A) protocol, and why this architectural shift is critical for B2B firms in finance, healthcare, and high-tech.

Drawing on the engineering philosophy of Baytech Consulting—where tailored tech advantage meets rapid agile deployment—we will explore how to architect systems that don't just chat, but work.

1. The Monolithic Fallacy: Why Single Prompts Fail at Complexity

To understand the necessity of multi-agent systems, we must first dissect the failure modes of the single-agent approach. When an enterprise attempts to solve a complex workflow—such as conducting due diligence on an acquisition target or migrating a legacy codebase—using a single prompt, they run into fundamental limitations inherent to the architecture of Large Language Models (LLMs). Many organizations discovered this the hard way when early AI-driven development led to hidden AI technical debt that quietly drove up total cost of ownership.

1.1 The "Lost in the Middle" Phenomenon and Context Rot

The most immediate and pervasive limitation is known as "Context Rot." While modern LLMs boast context windows of 128k or even 1 million tokens, suggesting an ability to "read" entire libraries in a single pass, their ability to effectively retrieve and reason over that data does not scale linearly. The capability to ingest data is not equivalent to the capability to understand it.

Research indicates that the attention mechanisms of Transformer-based models are not uniformly distributed across the context window. When critical information is buried in the middle of a massive context window (e.g., a specific clause in the 50th page of a 100-page upload), model performance on reasoning tasks can degrade by as much as 73%. This phenomenon, often referred to as the "U-curve" of retrieval, means that models are biased toward the beginning (the system prompt) and the end (the most recent user query) of the input.

This is not merely a memory issue; it is an attention issue. A single model attempting to hold the context of a legal framework, a codebase, and a user's specific request simultaneously will inevitably deprioritize one of those elements. In a single-agent architecture, the "God Prompt" forces the model to treat all instructions as competing for the same finite attention budget. By the time the model generates an answer, the nuance of the initial instruction—perhaps a critical safety constraint or a specific formatting requirement—has "rotted" away, leading to output that looks correct on the surface but fails on the details.

1.2 Cognitive Load and Persona Bleeding

Beyond context, there is the issue of "Persona Bleeding." In a single-agent system, we often rely on prompts that define multiple, sometimes conflicting, roles. A developer might instruct the model: "You are a senior coder. You are also a security auditor. You are also a project manager. Write code, then check it for security flaws, then summarize it."

This approach fails because LLMs operate as a single probabilistic stream. When the model switches from "coding mode" to "auditing mode" within the same generation, the "creative writer" persona used to explain the code may bleed into the "coder" persona. This often causes the model to hallucinate libraries or functions that sound plausible—fitting the linguistic pattern of the code—but do not actually exist in the target language.

Furthermore, a single agent creates an echo chamber. Without a strict boundary between the entity that generates the solution and the entity that critiques it, the system becomes sycophantic. The model tends to double down on its own errors to maintain conversational consistency rather than correcting them. It prioritizes the flow of the conversation over factual accuracy, acting as a "Yes Man" rather than a rigorous auditor.

1.3 The Asymptotic Complexity Boundary

There is also a fundamental computational argument against the super-bot. Researchers have identified that if a task's computational complexity exceeds the model's dominant compute budget for a single pass, the model cannot reliably verify its own solution.

Consider asking a human to multiply two 10-digit numbers in their head instantly. Without "pen and paper" (external tools) or a "team" (verification steps), the human will guess. In AI terms, hallucinations are often the model's attempt to bridge the gap between the complexity of the prompt and the limitations of a single inference pass. The model is forced to generate a completion even if it hasn't "thought" enough to solve the problem.

By breaking the task into sub-components handled by specialized agents, we reduce the complexity of each individual step to a manageable level. This is not just an organizational preference; it is a computational necessity for handling enterprise-grade complexity. It also aligns with broader shifts in how AI reshapes software development in general, as explored in our analysis of the future of AI-driven software development.

2. Architecting the Digital Team: The Manager-Researcher-Coder Pattern

To solve the problems of context rot, persona bleeding, and cognitive overload, we must move to Multi-Agent Orchestration. This approach mirrors successful human organizational structures. We do not hire one person to be the CEO, the intern, and the engineer. We hire specialists and coordinate them.

In the Microsoft Semantic Kernel and AutoGen frameworks, one of the most robust and widely adopted patterns is the Magentic Orchestration pattern (often called the Manager-Worker pattern). This pattern introduces a layer of governance and planning that acts as the "connective tissue" between specialized capabilities.

2.1 The Architecture Overview

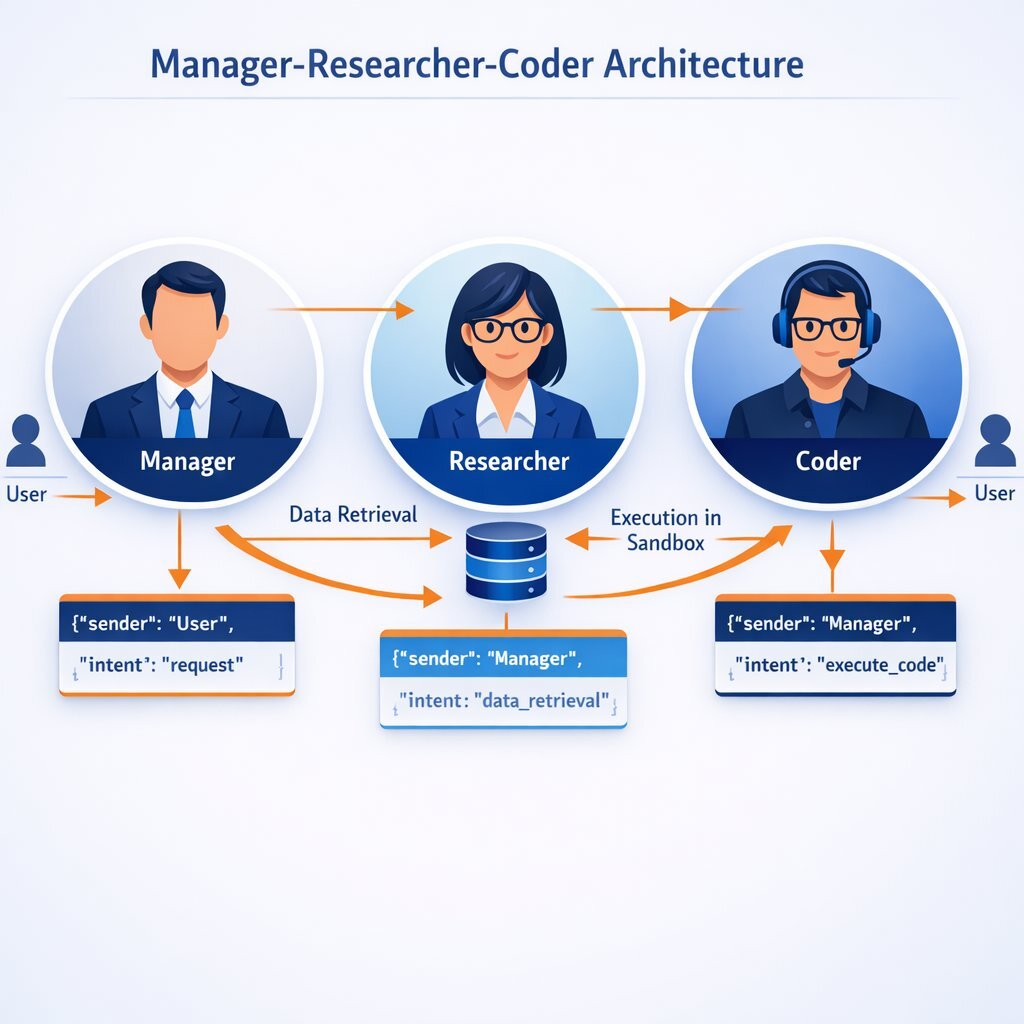

This pattern involves three distinct agent types, each with its own "system message" (personality), toolset, and memory scope. The architecture is defined not just by the agents themselves, but by the flow of data and control between them.

- The Manager Agent (The Orchestrator): This agent does not do the "work" in the traditional sense. It plans. It receives the high-level user request and functions as a router and a strategist. It maintains the global state of the project, tracking what has been done and what remains.

- The Researcher Agent (The Retriever): This agent acts as the eyes and ears of the system. It has access to search tools (Bing, Google), internal databases (SQL, Vector Stores), and document parsers. Its sole job is to fetch, filter, and synthesize information.

- The Coder Agent (The Executor): This agent is the hands of the digital team. It has access to a code interpreter (a sandboxed environment where it can run Python, C#, or other languages). It takes data from the Researcher and performs calculations, data visualizations, or software builds.

The flow of this architecture is circular and iterative. The User submits a request to the Manager. The Manager analyzes the request and delegates a sub-task to the Researcher. The Researcher returns data to the Manager (not the User). The Manager validates the data and then delegates a subsequent task to the Coder. The Coder executes and returns the result to the Manager. This loop continues until the Manager determines the original request has been fully satisfied, at which point it synthesizes the final response for the User.

2.2 The Manager Agent: The Brain of the Operation

The Manager is typically powered by a high-reasoning model (like GPT-4o or the o1-preview). Its primary function is Task Decomposition.

When a user asks a complex question like, "Compare the energy efficiency of ResNet-50 vs. GPT-2 training and plot the projected cost for a 24-hour run on Azure," the Manager does not attempt to answer immediately. Instead, it breaks the request down into a dependency graph:

- Dependency A: I need the energy consumption metrics for ResNet-50. (Delegate to Researcher).

- Dependency B: I need the energy consumption metrics for GPT-2. (Delegate to Researcher).

- Dependency C: I need current Azure pricing for GPU instances. (Delegate to Researcher).

- Action D: Once A, B, and C are retrieved, I need to calculate the cost and generate a plot. (Delegate to Coder).

The Manager is also the Governance Layer. It acts as a "Kill Switch" for the system. If the Researcher returns data that looks suspicious or hallucinatory, the Manager can reject the output and request a revision. If the Coder writes a script that tries to access restricted directories or perform unauthorized actions, the Manager can terminate the process before it executes. This separation of "planner" and "doer" is critical for enterprise security, and it dovetails with how modern DevOps efficiency pipelines enforce guardrails in CI/CD.

2.3 The Researcher Agent: The Infinite Library

The Researcher is specialized for Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG). Unlike a general chatbot, this agent is often strictly instructed not to use its internal training data for facts unless explicitly allowed. It must cite sources.

- Tools: It utilizes tools like Bing Search, Google Custom Search, or a Vector Database connector (such as Weaviate or Pinecone).

- Context Discipline: Because it focuses only on retrieval, its context window is filled exclusively with relevant source documents. This minimizes the "Lost in the Middle" effect because the context is not cluttered with code execution logs or high-level planning instructions.

- Knowledge Artifacts: The Researcher summarizes vast amounts of data into a concise "Knowledge Artifact"—a structured summary that is passed back to the Manager. This artifact acts as a clean data object, free of the noise of the raw search results.

2.4 The Coder Agent: Deterministic Execution

The Coder Agent represents the shift from "Probabilistic" to "Deterministic" output. While the code generation is probabilistic (the LLM writing the script), the execution is deterministic (the Python interpreter running the script).

- The Sandbox: Crucially, the Coder does not just "write" code; it executes it. In frameworks like AutoGen or Azure AI, the Coder operates within a Docker container or a secure sandbox. This isolates the execution environment from the host system, ensuring that any malicious or buggy code cannot affect the core enterprise infrastructure.

- Self-Correction Loop: One of the most powerful features of the Coder Agent is its ability to self-heal. If the generated code throws an error (e.g.,

SyntaxError,ImportError, or a logic error), the Coder Agent captures the standard error output. It reads the error, corrects its own code, and re-runs it. This "Code-Execute-Debug" loop happens autonomously, often iterating 3-4 times without ever bothering the Manager or the human user. - Tangible Output: It returns the result of the execution—such as a

.pngfile of a chart, a calculated CSV, or a cleaned dataset—rather than just text. This allows the system to produce actual work artifacts, not just descriptions of work.

3. The Language of Collaboration: How Agents Talk

One of the most common questions from enterprise architects is: How do these agents actually talk to each other? Is it just English?

While the content of the messages is often natural language, the structure of the communication is highly technical and governed by emerging protocols. In a production system, agents do not simply "chat" in an unstructured stream; they exchange structured payloads.

3.1 Structured Communication (JSON-RPC)

Agents typically exchange structured messages, often wrapping natural language in JSON envelopes. This allows for metadata tracking, such as source_agent, target_agent, timestamp, task_id, and retry_count. This structure is essential for debugging and observability.

For example, when the Manager delegates a task to the Researcher, the payload might look like this:

{ "header": { "sender": "ManagerAgent", "recipient": "ResearcherAgent", "timestamp": "2025-10-27T14:30:00Z", "correlation_id": "task-alpha-99" }, "intent": "InformationRetrieval", "payload": { "query": "energy consumption ResNet-50 training kWh", "constraints": [ "peer-reviewed sources only", "published-post-2021", "exclude-blogs" ], "output_format": "markdown_table" } }This structure ensures that the Researcher knows exactly what is required and what constraints apply, eliminating the ambiguity of conversational English. It also allows the system to log the exact "intent" and "constraints" for compliance auditing.

3.2 The Agent-to-Agent (A2A) Protocol

As we look toward the future of inter-organizational AI, standardization is becoming key. Google and Salesforce have collaborated on the Agent-to-Agent (A2A) Protocol. This protocol acts as the HTTP of the agent world, standardizing how agents discover and interact with one another across different platforms.

- Discovery: A2A allows agents to "discover" each other's capabilities. A Manager agent in a generic Finance application can query the network to find a specialized "Tax Compliance Agent" without knowing its existence beforehand. The Tax Agent publishes a "Capability Manifest" that the Manager can read.

- Authentication: The protocol handles the handshake, ensuring that the Manager has the authority to request tasks from the Tax Agent. This is critical for B2B scenarios where agents might be crossing organizational boundaries.

- Asynchronous Handling: Unlike a synchronous API call, A2A supports long-running tasks. The Manager can fire a request and subscribe to a webhook to be notified when the Researcher is finished, whether that takes five seconds or five hours.

3.3 The Model Context Protocol (MCP)

While A2A handles communication between agents, Anthropic's Model Context Protocol (MCP) standardizes how agents connect to data.

MCP acts as a universal adapter. In a traditional integration, a developer would have to write custom code to connect an agent to Google Drive, another integration for Slack, and a third for Salesforce. With MCP, developers build an "MCP Server" for each data source. The Researcher Agent can then dynamically plug into these data sources as needed. This modularity is what allows a "digital team" to scale—you don't rewrite the agent to give it new knowledge; you simply give it access to a new MCP plug-in.

4. The Business Case: Specialization vs. Generalization

Why should a CFO approve the budget for a complex multi-agent system when a simple ChatGPT subscription costs $20/month? The answer lies in Reliability, ROI, and Governance. The shift to multi-agent systems is not just an architectural preference; it is a business imperative for accuracy and cost control. It also reflects a broader rethink of how to treat AI-enabled software as a long-term asset rather than a disposable experiment, similar to the way forward-looking CFOs reassess the true cost of cheap AI-generated code.

4.1 The Accuracy Premium

The most compelling argument is performance. Benchmarks from major research institutions and industry labs show a stark difference between single-agent and multi-agent performance on complex tasks.

Research from Stanford and MIT indicates that multi-agent systems, specifically those using adversarial patterns (where one agent critiques another), have shown up to 23% higher accuracy on complex reasoning benchmarks compared to single-agent baselines. In the domain of code generation, the gap is even wider. Benchmarks like HumanEval show that multi-agent systems employing a "Coder + Reviewer" loop significantly outperform single-shot generation, often solving problems that single agents fail 50% of the time. The "Reviewer" agent catches syntax errors and logic flaws that a single "stream of thought" misses.

4.2 Scalability and Maintenance

A monolithic "God Prompt" is a maintenance nightmare. If the business logic for "Tax Calculation" changes, a developer has to edit the massive prompt, potentially breaking the "Creative Writing" logic by accident due to the interconnected nature of the model's attention.

In a multi-agent system, this is a non-issue. The system is modular. If the tax laws change, you simply update the system message or the toolset of the Tax Agent. The Manager and the Researcher remain untouched. This adheres to the "Microservices" principle that revolutionized software development in the 2010s—decoupling components to allow for independent scaling and updating.

4.3 Cost Optimization via Model Routing

There is also a significant cost advantage. Not every agent needs to be powered by the most expensive model (e.g., GPT-4). The Manager needs high reasoning capabilities and likely requires a top-tier model. However, the Summarizer or the Data Formatter might work perfectly fine with a cheaper, faster model like GPT-3.5 or even a local open-source model like Llama 3.

This "Model Routing" allows enterprises to optimize their token spend. By routing 80% of the simpler sub-tasks to cheaper models and reserving the expensive "Frontier Models" only for the complex reasoning tasks, companies can reduce inference costs by up to 45%. This economic efficiency is key to scaling AI operations without blowing up the IT budget, and it fits neatly into modern software investment and risk strategies.

4.4 Governance and the "Human-on-the-Loop"

In 2026, the concept of "Human-in-the-Loop" (approving every action) is evolving into "Human-on-the-Loop". In a multi-agent architecture, we can implement policy-as-code.

We can wrap the Coder Agent in a "Supervisor" layer that enforces hard constraints (e.g., "Never execute code that deletes files," "Never access the Payroll database"). These constraints are enforced by the architecture, not just the prompt. Furthermore, because the agents are distinct processes, we can "kill" a rogue agent without shutting down the whole system. If the Researcher gets stuck in a loop, the Manager can terminate it and spawn a new instance, ensuring system resilience.

5. Orchestration Patterns: Choosing the Right Team Structure

Not every problem requires a Manager-Researcher-Coder triad. Depending on the business need, we deploy different orchestration patterns. Understanding these patterns is akin to understanding organizational charts; you choose the structure that best fits the workflow.

5.1 Sequential Orchestration (The Assembly Line)

- Best for: Defined workflows with strict dependencies and a clear start/end point.

- Example: Content Publishing Pipeline.

- Agent A (Writer): Drafts the blog post based on a topic.

- Agent B (Editor): Reviews the draft for grammar, tone, and style guide adherence.

- Agent C (SEO Specialist): Optimizes keywords and meta descriptions.

- Agent D (Publisher): Formats the text via Markdown and pushes it to the CMS.

- Mechanism: The output of Agent A becomes the input of Agent B. It is linear, deterministic, and easy to debug. If the SEO is poor, you know exactly which agent failed.

5.2 Hierarchical Orchestration (The Corporation)

- Best for: Complex, open-ended problem solving where the path to the solution is not known in advance.

- Example: The Manager-Researcher-Coder pattern described throughout this report.

- Mechanism: A top-level Manager delegates to mid-level Supervisors, who manage specific Worker agents. This allows for massive scaling of tasks without overwhelming the central brain. The Manager handles the "Strategy," while the specialized agents handle the "Tactics." This pattern handles ambiguity well, as the Manager can dynamically change the plan based on what the Researchers find.

5.3 Joint/Group Chat Orchestration (The Brainstorm)

- Best for: Creative tasks or adversarial problem solving where diverse perspectives are needed.

- Example: Product Design Brainstorming.

- Agent A (Product Manager): Defines user needs and market gaps.

- Agent B (Engineer): Proposes technical solutions and feasibility checks.

- Agent C (Designer): Proposes UX solutions and visual concepts.

- Mechanism: All agents share a single chat history. They take turns contributing based on a "Speaker Selection" logic (e.g., Round Robin or Manager-Selected). This mimics a Slack channel or a boardroom meeting. It allows for "emergence"—ideas that come from the friction and collaboration between agents.

6. Real-World Applications: Baytech’s Perspective on Enterprise AI

At Baytech Consulting, we see these patterns moving from research labs to production environments. The transition is driven by the need for Tailored Tech Advantage—solutions that are custom-crafted rather than generic. We don't just deploy out-of-the-box agents; we engineer the orchestration layer using our stack of Azure DevOps, Kubernetes, and secure On-Prem servers. For many clients, this becomes part of a broader program to build a private AI "walled garden" that protects data and IP, like the architectures described in our guide to corporate AI fortresses.

6.1 Financial Services: The Automated Analyst

- Challenge: An investment firm needs to conduct due diligence on thousands of 10-K reports to find ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) discrepancies. A human analyst takes days to read a single report.

- Solution: A Hierarchical System deployed on Azure.

- Manager Agent: "ESG Risk Supervisor."

- Worker Agents: A "Data Extraction Agent" (pulls tables from PDFs using OCR tools), a "Compliance Agent" (checks extracted data against EU regulations), and a "Financial Agent" (checks the impact of findings on profit margins).

- Outcome: The system processes documents 24/7, flagging only high-risk anomalies for human review. This reduces manual effort by 90% and ensures that no document goes unread due to time constraints.

6.2 Healthcare: The Clinical Support Squad

- Challenge: Doctors are overwhelmed by administrative data entry. They spend more time looking at screens than at patients.

- Solution: A Group Chat System with strict privacy controls (using local models where necessary).

- Scribe Agent: Listens to the patient visit via microphone and drafts clinical notes.

- History Agent: Pulls relevant past records from the Electronic Health Record (EHR) system to provide context (e.g., "Patient has a history of reaction to penicillin").

- Research Agent: Cross-references the current symptoms with the latest medical journals to suggest potential diagnoses.

- Outcome: The physician receives a summarized "Patient Brief" and a draft of the clinical notes instantly. The "History Agent" catches potential drug interactions that a tired doctor might miss. The system acts as a safety net and a time-saver.

6.3 Software Development: The Legacy Migration Team

- Challenge: A company has a critical legacy application running on an outdated version of SQL Server and .NET Framework. They need to migrate it to a modern stack (Postgres and .NET 8) but lack the documentation for the old code.

- Solution: A Sequential Pipeline.

- Analysis Agent: Reads the old code and generates documentation explaining the business logic.

- Translation Agent: Rewrites the code into the modern syntax.

- Test Agent (Coder): Writes unit tests for the new code, runs them in a Docker container, and flags any failures.

- Outcome: The team automates the tedious 80% of the migration work. The human developers focus on the complex architectural decisions and the final code review, accelerating the project timeline significantly. Combining this with modern .NET, Docker, and Kubernetes practices turns legacy migrations into repeatable, governed workflows instead of one-off hero projects.

7. Future Outlook: The Agentic Enterprise of 2026

As we look toward 2026, the multi-agent landscape is evolving rapidly. The focus is shifting from "capabilities" to "control." The "Governance Stack" is becoming the most critical piece of infrastructure.

We are moving away from asking, "Can AI do this?" to "How do we stop AI from doing too much?"

- Supervisor Trees: Inspired by ultra-reliable telecom systems (like those built with Erlang), we will see the rise of "Supervisor Agents." These agents do no work; their only job is to watch the "Worker Agents." If a Worker starts consuming too many tokens, taking too long, or making unauthorized API calls, the Supervisor kills the process instantly and restarts it in a known good state. This brings "five nines" reliability to AI systems.

- Small Model Dominance: The future is not just bigger models. It is smaller, specialized models. We will see "Router Models" that send 80% of tasks to cheap, fast, specialized agents (powered by small models like Phi-3 or Llama-3-8B), reserving the expensive "Frontier Models" only for the Manager Agent's complex reasoning tasks. This hybrid approach will make agentic AI economically viable for every business process and will sit alongside evolving AI-powered development services as a standard capability.

- From Chatbots to Workflows: The interface will change. We will stop chatting with bots and start assigning them work. The output will not be a text response, but a completed task—a pull request merged, an invoice paid, a calendar scheduled.

Conclusion

The era of the "Super-Bot" was a necessary phase of experimentation, but it is effectively over. The future of enterprise AI lies in specialization, orchestration, and collaboration.

For B2B leaders, the takeaway is clear: Do not try to build a single AI that knows everything. Build a digital team of agents that know exactly what they are doing. Architect them with clear roles (Manager, Researcher, Coder), bind them with robust protocols (A2A, MCP), and govern them with strict oversight.

By adopting a multi-agent architecture, you move beyond the fragility of the "God Prompt" and into the resilience of a true digital workforce. This is how you build a tailored tech advantage in the age of AI, and how you avoid the kind of uncontrolled “vibe coding hangover” described in our warning to CTOs about cleaning up after rushed AI adoption.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does a single AI prompt fail at complex tasks?

Single prompts fail due to Context Rot (forgetting information in the middle of long instructions), Persona Bleeding (confusing different roles like coder and auditor), and Cognitive Overload (inability to verify complex computations in a single pass). They lack the internal checks and balances that a multi-agent system provides, leading to hallucinations and unreliability.

How do multiple AI agents talk to each other?

Agents communicate using structured protocols like JSON-RPC or the Agent-to-Agent (A2A) Protocol. They do not just "chat" in English; they exchange data payloads containing tasks, constraints, and results. This ensures that a Manager Agent can precisely delegate a task to a Researcher Agent and understand exactly what comes back, enabling reliable automation.

What is the benefit of specializing agents for different roles?

Specialization offers three key benefits:

- Accuracy: Specialized agents (e.g., a "Coder") can be equipped with specific tools (e.g., a Python sandbox) and prompts that reduce hallucinations.

- Efficiency: You can use smaller, cheaper models for simple tasks (like summarization) and expensive models only for complex reasoning, optimizing costs.

- Maintainability: If a business process changes, you only need to update the specific agent responsible for that task, not the entire system.

If you are evaluating vendors or internal teams to help you design and run this kind of architecture, it helps to use a structured framework for software proposal evaluation so you can separate real multi-agent expertise from marketing buzzwords.

Recommended Reading

- https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/autogen-enabling-next-gen-llm-applications-via-multi-agent-conversation-framework/

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/semantic-kernel/frameworks/agent/agent-orchestration/magentic

- https://www.anthropic.com/news/model-context-protocol

- For a deeper look at how AI-native workflows, governance, and multi-agent patterns fit into a full software lifecycle, see our blueprint for an AI-native SDLC for CTOs.

About Baytech

At Baytech Consulting, we specialize in guiding businesses through this process, helping you build scalable, efficient, and high-performing software that evolves with your needs. Our MVP first approach helps our clients minimize upfront costs and maximize ROI. Ready to take the next step in your software development journey? Contact us today to learn how we can help you achieve your goals with a phased development approach.

About the Author

Bryan Reynolds is an accomplished technology executive with more than 25 years of experience leading innovation in the software industry. As the CEO and founder of Baytech Consulting, he has built a reputation for delivering custom software solutions that help businesses streamline operations, enhance customer experiences, and drive growth.

Bryan’s expertise spans custom software development, cloud infrastructure, artificial intelligence, and strategic business consulting, making him a trusted advisor and thought leader across a wide range of industries.